Texts/Reviews/Interviews

MORE THAN VIOLET

Publisher: Art and Theory

Graphic design: Sandra Praun

Writers: Michael Famighetti, Julia Peirone

72 pp

Hardcover

Graphic designer: Sandra Praun, Designstudio S

English

ISBN 978-91-979985-1-2

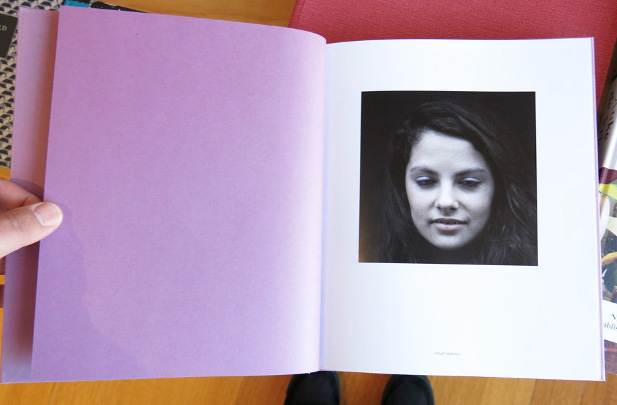

In this age of networked images, identity is increasingly constituted by images, both self-generated and produced by the media. We can experiment and play with our appearances, creating our own image of ourselves. The tradition of studio portrait photography on the other hand, has in general aimed to capture the sitter’s best self. In Julia Peirone’s intriguing images these two approaches intersect and collide. She shoots hundreds of frames, but eventually only selects the failed and usually discarded ones. Using the studio environment and context she undermines the idea of the photogenic.

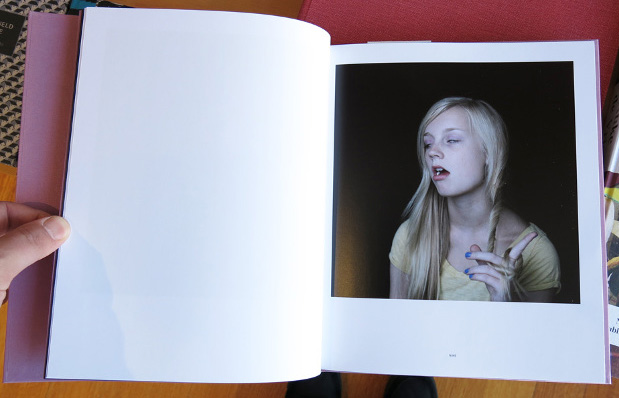

Technically perfect, but imperfect as portraits in the traditional sense, there is no “essence” of the portrayed in these images; they defy all conventions of how to conduct oneself before the camera. The viewer’s expectations in looking at young girls are also challenged here. Geared up for a studio portrait, long-haired and pale in their shimmering make-up, the girls could be regarded as beautiful, but their supposed beauty eludes the viewer; we are not allowed to get a good look at the girls. Their eyes are half closed mouths half opened, some are obviously chewing gum—indifferent yet aware of the gaze of the viewer, and thus paradoxically,a perfect depiction of teenage girls. Being a teenager is being in the in-between. Julia Peirone was born in 1973 and has had numerous exhibitions in Sweden and abroad.

Looks Like Teen Spirit

(Text by Michael Famighetti)

In the early days of photography, having a portrait taken could be traumatic. Sitters, who had to stay still for long exposures, were often dismayed to discover what they actually looked like. Unlike Narcissus who fell in love with his image reflected in a puddle, the detailed likeness produced by the camera could undermine a person’s vanity. The American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne remarked that he was “startled at recognizing [himself] apart from [himself].” However, in the age of networked images, when identity is at least in part constituted by images, both self-generated and those absorbed through media, we can play a fast and loose game with our image and photogeneity. It is normal to shoot endless images of ourselves, playact for the camera, and experiment with ugliness. Some iPhone apps work like an old carnival’s house of mirrors, allowing us to distort, contort, and pinch our faces, or even show us what we might look like bald. Imagining ourselves as grotesque provides pleasure. In a culture that places great stock in beauty, we can safely undermine our looks. The process might even make us feel better about what we actually do look like. This contrasts with the tradition of studio portrait photography that, generally speaking, has aimed to capture a sitter’s best self. Even if the studio has functioned in a wide variety of ways, as a site for fantasy and invention, the result has usually been either a flattering image, or at least a clear description of a face. The subject poses, and despite intervention from the photographer, chooses, to a degree at least, how she wishes to be seen. But what does it mean for a photographer to make formal studio portraits and then through her editing undo the subject’s role in posing and making the picture?

Julia Peirone points to a range of influences, from television shows like Top Model to Renaissance painting, as informing her series More than Violet, which uses the studio environment to undermine the idea of the photogenic. Peirone also cites the nineteenth-century English portraitist Julia Margaret Cameron as an influence. Cameron who photographed her circle of notables also photographed young girls, and her images were criticized for disregarding photographic conventions. One commentator dismissed them as “out-of-focus portraits of celebrities,” remarking that, “we must give this lady credit for daring originality, but at the expense of all other qualities.” Peirone’s images, however, are anything but romantic. There is nothing gauzy here. If anything, her portraits feel clinical. She doesn’t seduce the viewer by making her sitters appear angelic, nor does she invoke any mythology. Rather, she challenges the viewer by thwarting any of the expected rewards of looking at young girls. Like Margaret Cameron, Peirone disavows convention: to succeed these photographs must fail. Shooting hundreds of frames, she only selects those that might usually be discarded. We can assume that the discarded frames are those in which her subjects adopt a more expected, desirable pose that is the product of the sitter’s internal repertoire of images, be it a glamour shot or another model for posing femininity. Peirone instead offers us a series of awkward, unguarded moments taken when her sitters are unaware of the camera. Her young subjects’ eyes are closed, their mouths hang slack, appearing on the cusp of sleep, one frizzy-headed blonde, her eyelids weighted with makeup, looks drugged or on the verge of speaking in tongues. These images are aggressive, yet playful, and highlight photography’s fraught relationship with young women and how preconceptions formed by images influence how we comport ourselves before a camera. The obvious offenders for creating destructive examples are fashion and advertising, but fine art photography also falls into similar traps. Projects dealing with young girls, save some notable exceptions, have a tendency to create voyeur-ready Lolitas or claim to demystify young people, offer anachronistic ideas about penetrating a subject’s psychology or celebrating innocence, when they often do little more than circumscribe a subject by a viewer’s desire.

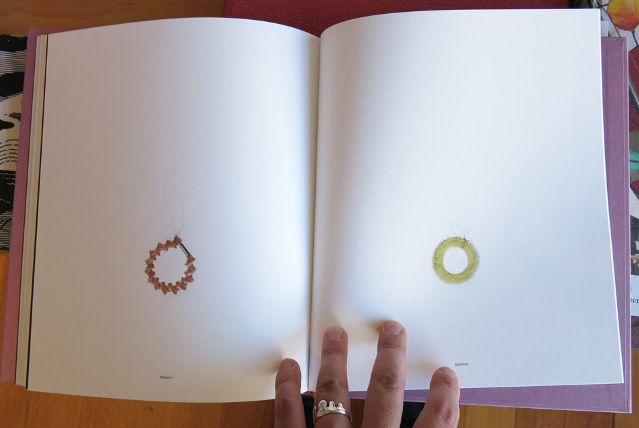

But aside from these refusals, what else do Peirone’s “failed” pictures tell us? As a series, they suggest a taxonomy of gesture particular to this cohort, as her subjects default to the same movements: anxious fingers twist thick shocks of hair and tug at jewelry; bubble gum inflates and deflates; hands linger with no clear place to rest. These are the weird, unscripted, unconscious gestures that their teachers probably observe in the classroom, movements and expressions that suggest interior lives, daydreams, and identities not defined by a viewer or by a body, nor by a memory bank of images. They tell us that the subject is present, but disinterested in a viewer. They seem to confirm Balzac’s defiant position on portraits, “Your plates…can only record some pose of my body.” A sentiment echoed a century later by Richard Avedon’s formulation that in a portrait “the surface is all you’ve got.” Peirone too rejects any enduring hang-ups about capturing “the essence” of the sitter, and while her pictures underscore problems in photography, they also tell us something about being a teenager, a time when the idea of being looked at is simultaneously thrilling and terrifying and when there is pleasure to be gained from being happily indifferent—in this case, indifferent and inscrutable to the gaze of the viewer.

The Flash blinds the moment

(Text by Julia Peirone)

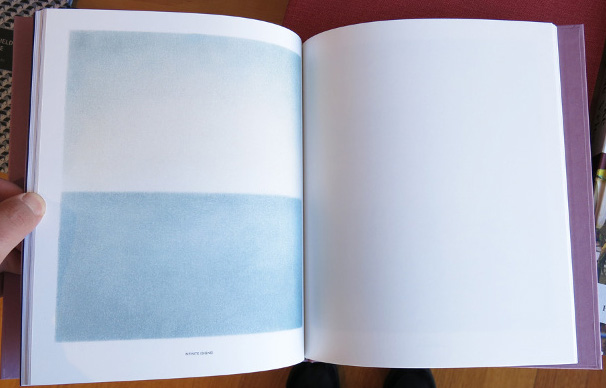

“Hi, I’m very interested!

Can you give me some more details?

My greatest wish is to become as famous and to work in the same field as Jennifer Aniston. I have many good qualities and I’m not shy and not afraid to stand in front of a camera. I have done gymnastics and horse riding. I have four younger brothers and sisters, so I know how to play different roles in a family. I dance a lot and love to perform. I also love to act like I’m someone else. For example when I talk to my friends I often sound like one of my idols. I have a very unique appearance and that’s why I enjoy being in front of the camera.”

She pulls her fingers through her hair and looks at me. How’s this? I focus on her eye and adjust the lens. Click click. Two moments later and the image of her disappears. The camera’s eye captures, once again faster than mine.A new attempt. She looks at me quizzically and asks, should I do anything in particular? Nothing, just stand there. Do you have a boyfriend? How’s school? I try to distract her. I think of everything, all at once; how I am fighting against a failure that I simultaneously have to surrender myself to; how I have to keep track of the frame and the composition inside it. I crop her hand, the gesture and now she blinks, the eye! I almost miss. Once more and I’ll have her. Her mouth is half open as if saying to me, I am not there but here, now. Take me!

I want to get in there, behind the pose, and distract her. She tells me about school and friends click, click. I snap, listen and look at her body. Her eyes flutter and her hands direct, I follow. Who is she? The camera protects and unfolds my curiosity. I stand with locked legs, trembling with tension, my body starts to cramp. Her body seems confused. The flash goes off again and again, creating a performance in the room. My arms hurt, the camera is heavy and my eyes are tired. Break! I stretch, take the rubber band out of my hair and rearrange my hairstyle. She does the same and her hair-band glitters in pink, cherry, just like the sea does sometimes. Strands of hair have become entangled and wrapped themselves around the rubber band; it looks like a scalp. Sleazy and dirty. Click click I am the hunter... She looks nervous and I say something funny, making her laugh click click click. A cheap trick, like her lip-gloss. It produces the picture, makes the picture. I sweat and look through the lens. Several images in a row, she relaxes and the room starts to disintegrate. The colorful makeup weighs down her eyelids. The white of the eye is exposed for a fraction of a second. She closes her eyes and the blue hue shimmers like the sky above the ocean. Towards an eternity, no time can be captured, click, click. A closed look and an open space resting on lines, lost out of control. The flash blinds my moment. Makeup powder settles on skin, sticks and falls down onto her clothes, onto the paper and forms a horizon.